PRESENTED BY

THE DOMESDAY BOOK OF DOGS

De-extinction of the Thylacine

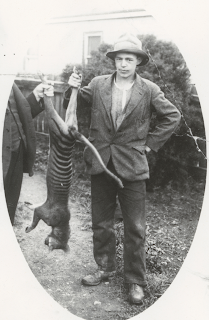

Thylacine killed by Clem Penny.

Courtesy of Libraries Tasmania, 1920.

PH30/1/6303

National Library of Australia.

The thylacine (Thylacinus

cynocephalus) was first sighted and recorded by European colonists in 1805, the

last known specimen died in captivity in 1936.

It took just one hundred and thirty-one years to completely wipe out the

world’s largest extant marsupial carnivore (about the size of a medium-sized

dog). The extermination was conducted on

an industrial scale with seemingly wanton cruelty and even as the species was

becoming scarce the killing carried on thanks to a government bounty

scheme. The thylacine ate only small animals,

there is even an account of an individual catching tadpoles (Paddle, 2000),

yet Tasmanian’s referred to it simply as ‘the tiger’, ‘the wolf’ or ‘the hyena’

and blamed it for ravaging the sheep population when feral dogs of near plague proportions

were the most likely culprits. The last

authenticated death of a thylacine in the wild occurred on 6th May

1930.

Life was tough for

the majority of Tasmania’s settlers who were for the most part callous and

largely unschooled, maybe they knew no better, but it’s the scientists of the

day who deserve all the opprobrium we can muster. They were helpless in the face of the

slaughter, and sometimes even indifferent to the plight of the thylacine. Myths of vampirism concocted as an excuse for

the carnage were seized upon and, in the early twentieth century, actually

entered into scientific construction. Perhaps

worse, healthy potential breeding stock were taken from the island and placed

in ‘solitary confinement’ in zoos around the world. Any attempts at breeding were at best haphazard

and cack-handed and at worst inept or even negligent and suffered, in many

cases, from a distinct lack of finance, space or common-sense.

Of later years the remorse and sense of loss

are palpable. Since 1936 there have been hundreds of ‘sightings’ both in

Tasmania, and mainland Australia where, it’s believed, the species became

extinct over 3,000 years ago. Sadly, any

photos tend to be blurry, even suspicious.

Nowadays there is a growing body of scientists who believe that cloning

would be feasible. Professor Mike Archer

first proposed cloning thylacines in the 1990s and the technology has come on

by leaps and bounds in the intervening years.

In 2009 Penn State University successfully sequenced the mitochondrial

DNA of two individuals: where once it was thought that the DNA would be too

badly degraded researchers have discovered that it is much more viable when extracted

from hair or teeth. An alternative to

cloning, CRISPR-Cas9, allows easy, cheap DNA editing and this could be a route

towards recreating the thylacine, possibly using genetic material from the quoll

or numbat as a foundation. This most

unique, distinctive and fascinating species (effectively a marsupial dog), pitilessly

wiped out by humans, may yet return.

|

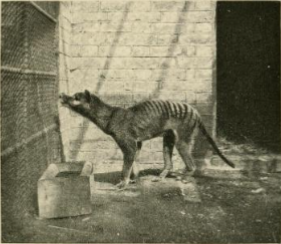

| Thylacine. Renshaw, 1905 |

--- Explore further ---

London. Sherratt & Hughes. 1905

Amy Spurling. E&T. 2018.

Comments

Post a Comment